|

General Information |

|

Quick Facts

Name: Beachy Amish Mennonite Church

Religious tradition: Beachy Amish-Mennonite ► Amish (1693-94) ► Anabaptist (1525) ► Christianity

North American population: 12,960 members in 201 congregations in the United States and Canada (2012).*

Global population: 1,000 to 1,500 members in around 75 congregations in Latin America, Europe, Africa, and Oceania.*

Most populous states: Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, Kentucky, and Tennessee*

Origin: From the 1920s through the 1950s, Old Order Amish disagreed over two major matters: first, whether to shun members who switch to a less conservative plain church, like Mennonite, and two, whether modern conveniences such as automobiles, electricity, telephones should be permitted for members’ private use. While Old Order Amish arrived at different conclusions about shunning, most forbid modern conveniences. Those that wanted neither a strong shunning nor a proscription against modern conveniences left the Old Order Amish and established a new Amish-Mennonite affiliation, the Beachys (the last name of an influential leader). In the 1950s and 1960s, the Beachy Amish-Mennonites adopted an evangelical / mission orientation, appealing to ex-Amish sympathizing with this orientation.

Institutions and Non-Profit Organizations (select): · Amish Mennonite Aid (church planting in developing countries) · Mission Interests Committee (church planting in developed countries) · Faith Mission Home (Virginia), mentally handicapped children’s home · Hillcrest Home (Arkansas.), retirement facility · Mountain View Nursing Home (Virginia), retirement facility · Calvary Bible School (Arkansas), post-secondary Bible institute · Calvary Messenger, primary periodical · Christian Aid Ministries, conservative Anabaptist para-church relief agency.

*Facts include all Amish-Mennonite subgroups related to the Beachys. See Amish-Mennonites and Other Plain Anabaptists page.

The First Beachy Amish-Mennonite Church The Beachy Amish-Mennonite affiliation has diverse origins in numerous states. As the Amish faced innovations of the twentieth century, they grappled with what to allow and what to forbid. The Beachy Amish-Mennonites were those Amish, a minority at the time, that were more (though not entirely) open to modern innovations like the telephone, automobile, farm tractor, and electricity, though not radio or television. The events in one congregation in south central Pennsylvania precipitated the movement, though undoubtedly there still would have been a Beachy Amish-Mennonite church without this particular event, given the movement’s widespread emergence. In 1881, the Amish community in Somerset County, Pennsylvania, with members in both Pennsylvania and Maryland, built four meetinghouses, two in Maryland and two in Pennsylvania. Many Amish do not have meetinghouses. Services were held in rotation in these four meetinghouses. In the mid 1890s, the more progressive group in Maryland wanted to have Sunday school, a Protestant phenomenon today rejected by the most Old Order Amish. Between 1893 and 1895, a separation took place between the Maryland and Pennsylvania groups. The Maryland group became Amish-Mennonite (though of an earlier Amish-Mennonite affiliation than the Beachy type of Amish-Mennonites). This division gave rise to a question facing many Old Order Amish across the country at this time: should members who transfer to the less strict Amish-Mennonite churches be shunned? Joseph Witmer, a visiting Amish bishop, assisted the Pennsylvania group. He did not support the strict shunning, where members were shunned if their only “offense” was transferring membership to the Amish-Mennonites. When Moses D Yoder was ordained bishop in 1895, Witmer relinquished oversight, as is common practice. Moses D Yoder felt the strict shunning should be implemented, and his congregation agreed to support him at that time. In 1912, Moses Beachy was ordained to the position of minister. In 1916, Moses Yoder was old enough that he accepted the position of inactive bishop. An ordination to replace Moses Yoder was held and the lot fell on Moses Beachy. Beachy did not agree with the strong shunning. However, he also wanted to have peace within the congregation. Noah Yoder and Joseph Yoder, both close relations to Moses Yoder, were Beachy’s co-ministers. Sometime in the early to mid 1920s, John D Yoder, a member of the local Amish church, inquired about whether he would have to shun those who went to the Amish-Mennonite church. When informed that he must, he also joined the Maryland church. However, Moses Beachy refused to instate the shunning since there was no longer unanimous agreement on the strict shunning. Tension increased between Beachy and the three Yoders, as well as among members. Communion was not held in the fall of 1926, a sign of lingering difficulties. In spring 1927, Moses Beachy pushed for communion despite ongoing disagreements. When held, only Beachy’s supporters assembled. In late June, the Yoder group announced the next service's meeting place at a different location than what Moses Beachy announced. Thus, on June 26, 1927, the Yoder group withdrew from the Moses Beachy group and the division was complete. Since the Establishment of the First Beachy Amish-Mennonite Church Within two years of June 26, the Moses Beachy group allowed electricity, vehicles, and Sunday school. The Moses Beachy group continued to alternate usage of meetinghouses with the Old Order Amish, and the two groups cooperated well in the years thereafter. Moses Beachy met with Bishop John Stoltzfus of Lancaster County, PA, shortly after the division. Stoltzfus' group had divided with the Amish 1909-10 over the strict shunning and telephones. When Stoltzfus and Beachy met, the Lancaster church had also just allowed automobiles. The two churches maintained close contacts, though official fellowship was not established until about a decade later, at that point a merely ceremonial act. These churches were Amish-Mennonite, but not as progressive as earlier Amish-Mennonite churches, such as the one established in Maryland. The 1940s marked a time when many new Amish-Mennonite congregations formed over issues of modern conveniences. These emerged in Virginia, Ohio, Indiana, Iowa, Ontario, New York, and elsewhere in Pennsylvania. Moses Beachy provided bishop assistance to many of these congregations; hence, they informally took on his name as “Beachy” Amish-Mennonite churches. In the 1950s, an evangelical / mission-oriented mindset grew in many congregations, partly under the influence of conservative Mennonite churches who had embraced evangelical theology for several decades. Out of the Beachy Amish-Mennonite’s mission interest came Amish-Mennonite Aid (AMA) and the Mission Interests Committee (MIC). Mid-century saw the establishment of foreign Beachy Amish-Mennonite churches in Germany, Belize, El Salvador, Costa Rica, and Paraguay. Domestic care units were formed over the same period, including voluntary service nursing homes like Hillcrest Nursing Home and Mountain View Nursing Home, and a children’s home for the mentally handicapped, Faith Mission Home. The Beachy Amish-Mennonites also held annual meetings for ministers (Minister’s Meetings) and for youth (the Youth Fellowship Meetings). Calvary Bible School for young adults and the monthly periodical, Calvary Messenger, were both started in 1970. These programs and institutions provided focal points around which the formerly loosely organized constituency could concentrate their energy, connect with people in other states, and forge a common vision. Yet, the new evangelical theology, with its emphasis on personalizing many aspects of faith, and access to greater technology, which gives one greater control over his environment, information, and mobility, tended to have an individualizing effect on the Beachy Amish-Mennonites that would challenge the primacy of church community so highly valued among the Old Order Amish. The primacy of church community is also largely responsible for enabling plain churches like the Amish to maintain a distinct set of Christian practices across multiple generations. Thus, from the 1960s on, the Beachy Amish-Mennonites have grappled with where to draw the line on numerous issues. In the 1990s, Beachy Amish-Mennonite leaders took steps to try to tackle concerns over eventual assimilation. A bishop committee was formed to investigate and propose action. The committee proposed a constitution outlining minimum guidelines for church membership in the constituency, but a minority of progressive churches blocked its adoption. The Beachy Amish-Mennonite ministers did succeed in adopting a statement against radio and television in the late 1990s. Implementing revisions in individual institutions were more successful. To address concerns about young adult religious deviance, Youth Fellowship Meetings were subdivided into regional groups to attempt to limit size of the meetings so hosts can keep better control. Meetings of several hundred attendees were reduced to under 100. A screening process for admission into Calvary Bible School was enacted. Nevertheless, these actions were not enough for some. The relatively loose structure of the Beachy Amish-Mennonite affiliation permitted several clusters of congregations to start working more closely together. These subgroups hold their own ministers’ meetings and other functions separate from the main body of the Beachy Amish-Mennonites. The "Maranatha Amish Mennonite" group was the most direct response to the non-adoption of the bishop committee’s proposed constitution. The Maranatha churches expressed concern over the lack of accountability among Beachy Amish-Mennonite churches and the inability to halt changes in dress, media, and technology. Maranatha Amish-Mennonite has a constitution that details minimum requirements to join, but otherwise retains the autonomy that characterizes the Beachy Amish-Mennonite constituency. Other groups, longer removed from the nucleus of Beachy Amish-Mennonite activity, did the same, adopting a constitution that fit their churches and developing nurture programs like youth meetings and outreach programs to serve their people. These include the Ambassadors Amish-Mennonite, Mennonite Christian Fellowship, Berea Amish-Mennonite, and Midwest Beachy Amish-Mennonite. To read a more detailed history of the Beachy Amish-Mennonite churches: Ž Read the Global Anabaptist/Mennonite Encyclopedia Online article Ž Purchase the coffee table-style book, The Amish-Mennonites of North America, which is a hardcover book with photos of church buildings and adherents, a brief history of every church, maps, and an essay on their history. (See the General Library and Archives listing for more information.) Ž Browse the General Library and Archives for works of topical interest.

|

|

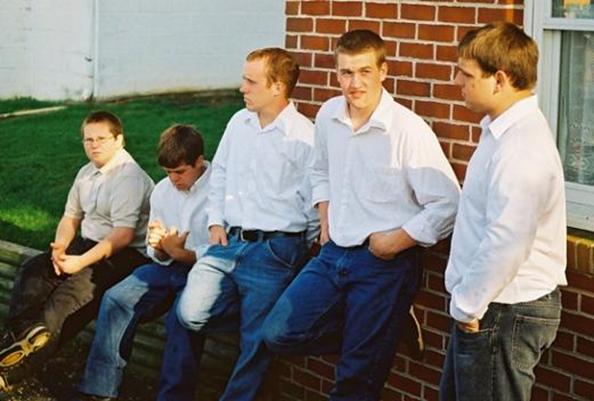

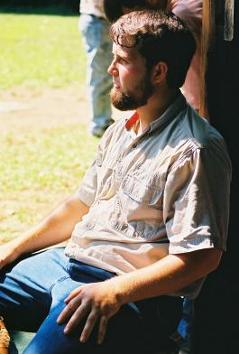

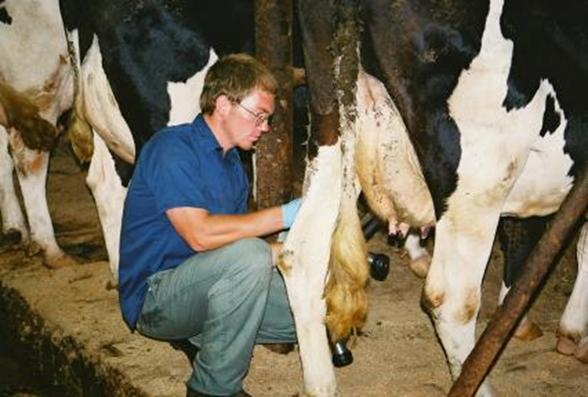

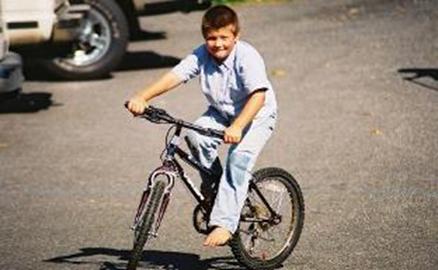

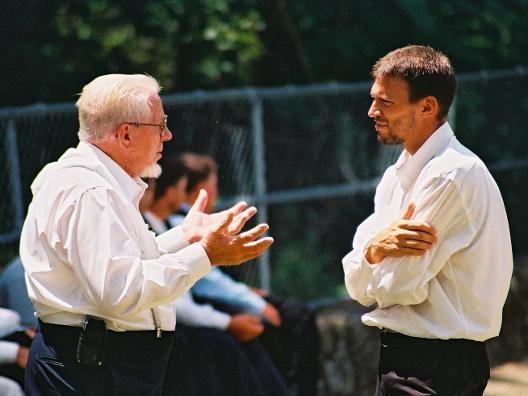

Candid Photographs of Beachy Amish-Mennonite Life and People |